Brahe & Kepler

When people ask me why we wanted to start Keen, I tell them this story of two scientists.

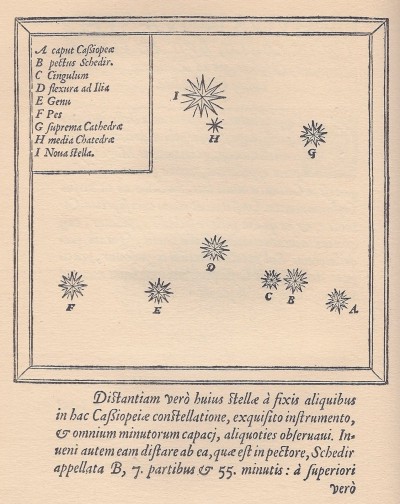

Tycho Brahe was a Danish astronomer in the 16th century. You probably haven’t heard of him. He wasn’t a great physicist or mathematician, but he had a really important insight, which was that the astronomers of the day were spending a lot of time working with really bad data. The data was longitudinally large (hundreds of years of star charts, handed down through the ages), but crappy. Brahe realized that he couldn’t draw useful conclusions from poor data, so his first step was to re-instrument the universe with the right data model. In each of his nightly “data snapshots,” Brahe wanted to document the position, motion, and brightness of every single celestial object in the sky.

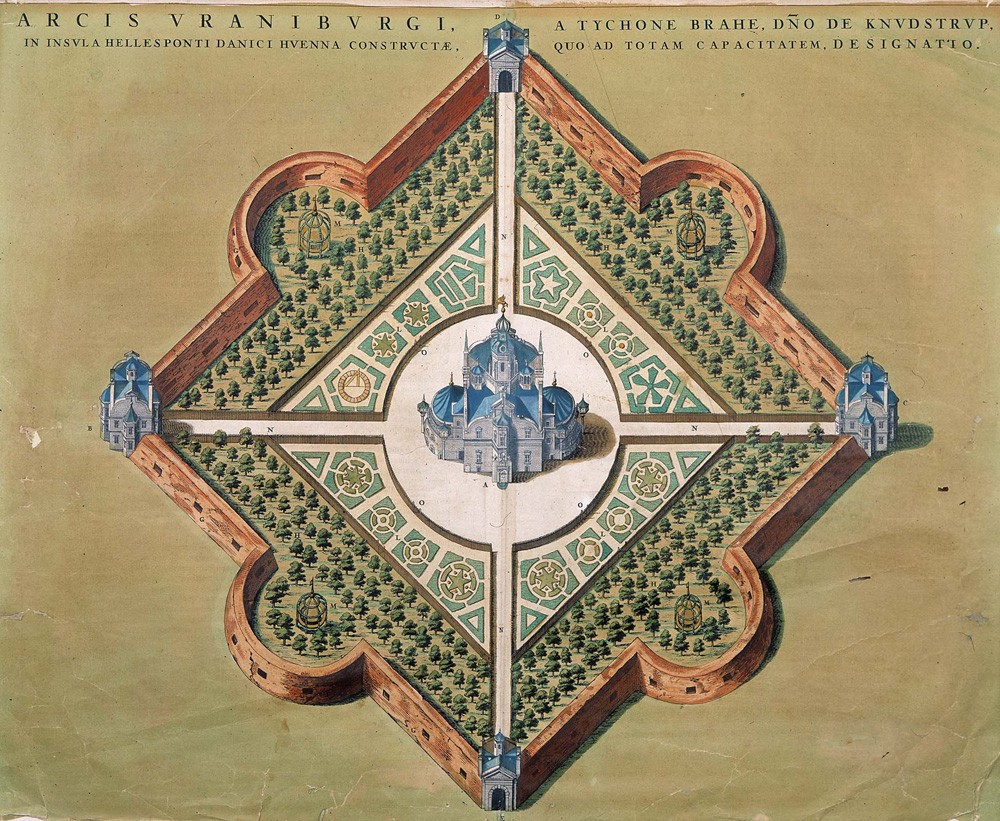

To accomplish this, Brahe built several versions of his own observatory from scratch. He built all his own instruments, and he kept such extensive records that he even built his own paper mill just to keep up — data storage wasn’t quite as cheap back then as it is today. And after sacrificing much of his fortune (plus over 30 years of nightlife), he suddenly died.

Luckily he had an assistant named Johannes Kepler. You probably have heard of him. Kepler spent over 20 years running calculations on Brahe’s data. In the end, he devised the laws of planetary motion, which inspired the work of Newton and Einstein and the foundation of modern physics.

According to NASA, Kepler’s work “launched the scientific revolution.”

Historical data not only helps us study the past, but it allows us to figure out the laws of our universe, which provide our only glimpses into the future. Powerful stuff, that historical data!

The Digital Observatory

Brahe was always the person in this story that stood out to me. He wasn’t a scientific genius and isn’t remembered by very many people, but in my book he was every bit as impactful as the famous Kepler (moreso, even — many Kepler-level thinkers had probably come and gone, but it wasn’t til one worked with Brahe that things fundamentally changed).

Brahe, armed with a custom-built observatory, was just a really practical, methodical, large-scale record-keeper — with high standards for precision and a very broad data model.

That’s pretty much what Keen is, too.

Keen is the modern observatory for the digital universe. The trillions of data points our customers are collecting will be the foundation for their future discoveries.

Observatory Design Considerations

The most important factors in building a good observatory are:

- the field of view

- the precision of the instrumentation

- the breadth of the data model

Beyond that, the most important factors for making those future discoveries more likely are the portability and the accessibility of the data.

Humanity was lucky that Kepler happened to work onsite with Brahe, because physical reams of paper aren’t all that portable.

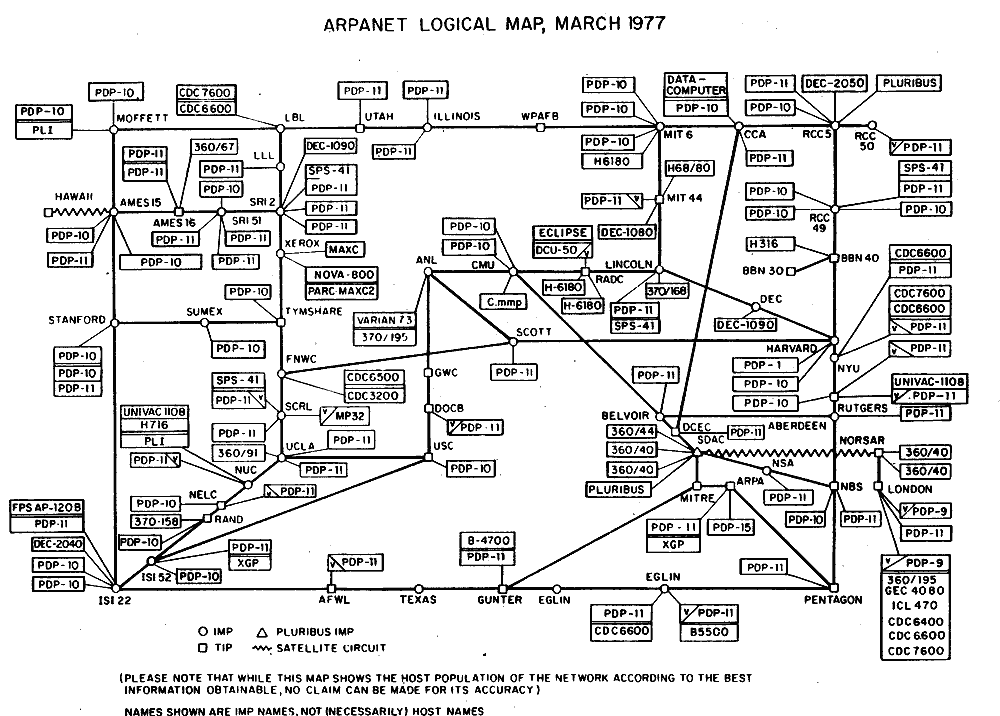

Fortunately, thanks to the Internet, a modern observatory could transcend such physical barriers. Imagine a cloud API that modern Brahe-like people can use to measure their worlds. And every one of those Brahe-like people would be able to expose their data to far more than one Kepler-like person.

APIs

These concepts of portability and accessibility are the reason we took an API-first approach to designing Keen.

In data systems generally:

Portability is high if I can get all or some of the data into other systems easily, and higher still if the form of those other systems can be arbitrary. The highest level of portability in a data system would be an API for extracting full-resolution chunks of the data, combined with an API for streaming the data out wholesale.

Accessibility of the data is higher through a Twilio-inspired REST API like Keen Compute versus, say, a giant and arcane data lake stored in SAP or Oracle or HBase or Teradata. In the latter, the data is guarded by a department full of data adepts, who require lots of meetings before maybe choosing to spend months of magician-time to give you an answer. In those sorts of systems, the API to get to that data is meetings + corporate politics + waiting around. The API into Keen data is, errr, an actual API.

This is nice for humans who want answers, but it’s even nicer for applications that want answers, since applications can’t have meetings or play politics. All they can really do is use APIs.

To put it another way, a well-abstracted REST API provides extremely high data accessibility to anything connected to the internet. When developers use those APIs to build data into software, we can achieve an even higher level of information accessibility. The beauty of making data-powered applications is that developers can put data into the hands of ordinary people. They don’t have to be Keplers.

Software Developers

As Marc Andreessen famously wrote, software is eating the world. What he really meant is that software is taking over the economy. Yes, leave it to a VC to accidentally conflate the economy with the whole world — but still, his point has merit.

If he’s right, then that means software developers will have an enormous responsibility in architecting the future economy. Developers will be its carpenters, its plumbers, its masons, its general contractors, its architects. They will build its bridges, its cities, its transportation systems, and its parks. Developers will build an increasing percentage of everything, and build into everything.

And increasingly, developers will choose which tools & technologies they build it with.

The things (products, apps, businesses) they build will be increasingly intelligent, in a variety of ways. One of those ways is that these things will have a sense of history. You might call them “history-aware products” or “history-aware applications” or “history-aware businesses.”

A Sense of History

Imagine you’re a software application.

You’re a bunch of bits of code and logic, creating and consuming an intricate symphony of information.

Got it? Good.

Now, what would it mean for you to have a sense of history? To be history-aware?

In my view, it doesn’t merely mean that you have a good memory, although that’s important. A good memory means you’re aware of — and can recall — what’s happened in the past. A perfect memory would allow you to instantly recall arbitrary facts in perfect detail.

Imagine you (the application) are running on a Fitbit in the year 2020. Every Fitbit in the world is running one of your brothers or sisters. Perfect memory would mean you know the answer to questions like these: What was the 90th percentile heart-rate of audience members during that one perfect scene in that one amazing horror movie? Was it different depending on time of day? On which theater they were watching in? On how much alcohol they had consumed beforehand?

Perfect memory alone is clearly powerful. And being able to access your entire tribe’s perfect memory just by issuing an API call is a superpower. As an application, calling an API is as trivial for you as it would be for a human to speak a word of English.

But to be history-aware isn’t just about knowing what happened in the past. More broadly, it means you’re aware that history exists as a concept.

What would it mean for you, the software application, to be history-aware in this way?

Not only would you remember all the events that happened previously and be able to run calculations across them, but that you would record your own observations in detail (like Brahe), so that in the future, other history-aware applications (including yourself in a future timeline!) can possess that same kind of perfect memory. For its members to have perfect memory, the entire tribe has to diligently record events as they pass.

Being a smart citizen means being aware of the history that’s already occurred. Being a good citizen means being history-aware in this broader context.

If you were a software application, this is a superpower you would probably find compelling.

Looking Forward

Much of the future economy will be built by developers. With great data tools and a sense of history, developers will not only make us contextually smarter, they will lay a foundation for ongoing discovery.

At Keen, our mission is to provide a ready-made digital observatory so that they don’t have to spend years building one like Brahe did.

The future is a place where anyone can study their universe or, like NASA did when they took Keen for a one-day spin, discover a pattern that has been eluding them for over a decade.

(And I think Kepler would find that pretty rad.)

Thanks to Michelle Wetzler, Micah Wolfe, Patrick Woods, Seth Bindernagel, Ursula Ayrout, inconshreveable, Sunil Dhaliwal, Ryan Spraetz, and Elias Bizannes for editing help.