Hi, I’m Michelle. I recently left my job as a technical consulting manager and joined my best friends and my fiancé, Kyle, at Keen.io. This is the story of how I negotiated my compensation.

When I started thinking about joining Keen, I quickly realized there is a lot I don’t know about startups. I’ve picked up quite a bit just by being around our CEO, Kyle, for the past few years — he’s been in and out and up and down in startups, and has shared some of the hard lessons he learned along the way. For example: Don’t accept equity compensation (stock shares) without knowing the percentage of the company you’ll own. Job titles in new companies are basically meaningless, so don’t be impressed or intimidated by them. And if the CEO says, “Salaries will be adjusted to market value soon,” that’s probably a best-case scenario.

So I knew a little bit. I knew enough to know I wanted to join a startup. To be honest, I knew I wanted to join this startup. The founders had been dropping hints that they wanted me to join them. We’d already discussed some of the work I could do for Keen. I hoped an offer letter was coming soon.

My big open question was, “How will I know if the offer is a fair one?”

To begin answering this question, I started on a quest to understand startup financing. First, I read Venture Deals by Brad Feld. This book was written to help founders negotiate financing with investors, but it really helped me understand Keen’s financial situation, and I highly recommend it to anyone joining a startup.

From there, I began googling things like “first employee startup equity” and “startup offer negotiation.” These were the best resources I found:

- Equity for Early Employees in Early Stage Startups

- Paul Graham’s Equity Equation

- How to Think About Cash vs. Equity Compensation

- Startup Equity for Early Employees

Meanwhile, the Keen founders, having just moved back to San Francisco after three months away at TechStars, met in our living room late one April evening and prepared offers for me and two of our other close friends, Kirk and Micah.

The next Monday, I received the following email from Kyle. He sent it to me from his desk in the Keen office, which is about eight feet from my desk in Keen office, which is in our house.

I knew this meant that the founders had come to some conclusion about what to offer, and now I was going to find out what it was.

Kyle sent a similar email to Micah that morning, and I crossed paths with Micah as he was leaving the meeting I was about to walk into. Micah is one of my best friends and one of our roommates since college, so we were in pretty similar situations.

Me: “How’d it go?”

Micah (smiling): “Good! It was interesting. They’ve really thought a lot about this and have some nice perks in mind, like reimbursements for the gym, and a rent subsidy for living near the office. And they gave me a choice whether I’d want more stock or a higher salary.”

Me: “Cool. I don’t really know what to expect. It’s so weird to be negotiating my salary with our friends. I prepared this list of questions…”

Micah (frowning): “Oh. I didn’t prepare at all… I guess I should have.”

Me: “Nah, it’s just the way I am. This is so weird. Later.”

I headed on to the bar with my be-doodled notebook and my questions, grabbed a beer from the bartender, and made my way out to the garden where Kyle was waiting for me with our little dog, G.

I called G to sit on my lap, and we listened. Kyle had a lot of things to say about how he wanted to build a great company. It is something he is truly passionate about and something we have discussed for years. Kyle talked about how he wanted to build a place where everyone loved to work, where everyone loved to learn, and where everyone was given the opportunity and the encouragement to do so. Eventually, we got around to the offer itself:

70k with .5% equity or

60k with 1% equity or

50k with 1.5% equity or

40k with 2% equity

Kyle is the most experienced offer-negotiator that I know. I told him that, if I got this offer from any other company, he’d be the first person I would ask for help. Obviously, though, that wasn’t going to work in this situation.

On the one hand, Kyle’s negotiating experience gave me confidence that the offer I’d received was pretty fair. Kyle has gotten enough offers himself to know what fair and unfair look like, and I trusted him and the other founders not to offer their friends something truly unreasonable. On the other hand, this was new territory for the founders as well; they had zero experience making offers to new startup hires.

Another thing that made this situation complicated was that Kyle and I are recently engaged. As a founder, his salary was lower than any of those offered to the new hires; he also had substantially more equity. But would it make sense for both of us to take that route? I talked with him about our specific options, and what would work best for us, together:

Michelle (me): “What should I do? It seems like I should take the highest salary and the lowest equity. When we combine our resources, that gives us more cash and still a lot of equity.”

Kyle: “Well you know me — I would take the high-risk, high-equity option. But I think your reasoning makes sense for the two of us.”

Michelle (half-kidding): “I feel like we need to write a pre-nup in order for me to do this analysis. Let’s go home.”

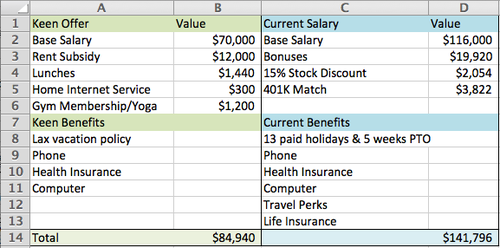

Back home, I took some time by myself and began to really think the offer over. I created a simple spreadsheet comparing my current compensation with Keen’s offer:

I also created an itemized budget for me and for Kyle, to estimate what our shared financial situation would look like for the year. This helped me determine that we could afford our current lifestyle even if I took a lower salary, allowing me some flexibility in my choice. Ultimately, however, I decided to play the safe option and shoot for a higher salary with less equity.

Kyle taught me never to take the first offer, though. It’s just a starting point, and you should always try to get more.

So, my next step was to prepare a counter-offer.

I used some of the equations I found online to try and determine a fair offer. True to my consulting roots, I made yet another Excel spreadsheet, plugging in the equations and the variables I found in the blogs mentioned above. This allowed me to tweak the inputs to understand the relationships between variables, and ultimately find some answers that made sense. Here are the three models I used, and their results:

Model 1: Paul Graham’s Equation: “In the general case, if n is the fraction of the company you’re giving up, the deal is a good one if it makes the company worth more than 1/(1 — n)” [Source]

Inputs:

– Employee’s value-add to the company (I used 15%, which I think is pretty low!)

– Employee’s annual rate (I used my current salary, plus bonuses)

– Company’s valuation (I used $5M, the cap for Keen’s seed note)

– Profit on the employee (I used 150%)

Result: A fair offer would be 2.67% of the company.

Model 2: Market Value Compensation: “The loss of compensation for the early employee as compared to market rate should be viewed as equivalent to the equity for that same dollar amount from an investor.” [Source]

Inputs:

– Employee’s market salary (I used my current salary, plus bonuses)

– Salary offered by the startup (I used my offer, plus benefits like rent subsidy)

– Company’s valuation (I used $5M, the cap for Keen’s seed note)

Result: A fair offer would be 1.14% of the company.

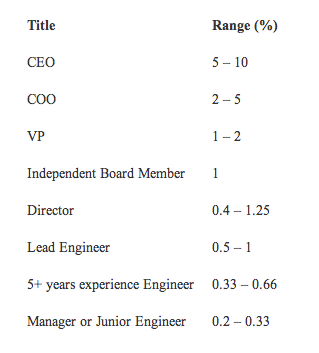

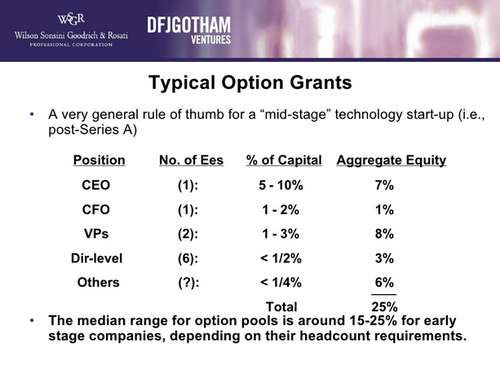

Model 3: Industry Standards Comparison

Lastly, I looked at some industry standard charts like these. Although I wasn’t sure of my exact position at Keen, I figured that I’d be somewhere around Director level. [Source]

Note: “These are post-Series-A numbers [Keen hasn’t raised Series A yet]. If the company is pre-funding or only has a small friends-and-family seed round, then the numbers should go up from there, based on expected dilution and greater risk.”

Assumption: The pre-dilution amount prior to Series A should be approximately double the amount in this post-Series-A chart.

Result: A fair offer would be between .8 and 2.5% in equity.

These results told me that Keen’s offer was in the right ballpark, but still a bit low.

In the meantime, Kirk and Micah were evaluating their offers, which were identical to mine. Kirk flew into San Francisco from Seattle on that Friday, so he could talk to the founders in person.

This was such a strange situation for all of us. We were competing against our best friends for slices of a shared pie. The more we negotiated for ourselves as individuals, the less there was for the founders, for each other, and for future employees. If this were like one of the strategy board games we regularly play, I’d be trying to win at all costs, giving my friends bad advice and hoping they’d screw up their trades. In this game, however, where the stakes were much higher, I found myself caring deeply about everyone getting a good and fair outcome, and not so much about getting the best possible deal for myself. I shared my spreadsheets and calculations with Kirk and Micah, and we talked with each other throughout the negotiation process. Kirk was leaning towards a high-risk, high-equity option, and Micah was somewhere between Kirk and me.

I have to admit, I was still struggling to understand what the numbers really meant, though. What is the difference between .5% and 2% equity in the long run? To try to answer that question, I built yet another model in Excel. This time, I was looking more closely at Keen’s cap table and various financial events, like raising Series A, becoming profitable, and company acquisition. Kirk and I soon realized we were both trying to do this in parallel, and I shared my spreadsheet with him.

Finally, having done our best to examine the numbers from every possible angle we could manage ourselves, we did something that is probably pretty unusual for a startup — or any company, for that matter. We had a big team meeting, with all three founders and all three potential new employees. We asked the founders to talk us through the financials, help us complete the detailed cap table, and discuss the offers together. We modeled various financial outcomes on the whiteboard and discussed the strategy for the employee pool.

We took a break in the middle of the day, and the three potential employees had a chat in the backyard. We joked about colluding against the founders and negotiating as a unit. Kirk was still unsure if he should be considering the offer at all, which for him meant leaving a new VP-track job at Amazon, giving back a signing bonus, and moving to California.

Kirk and I had already concluded that joining Keen was not in our best interests, financially. Our expected net worth after a few years in our existing management positions was, by any practical estimation, the most financially sound outcome — and a very good one, at that. Even if things went great at Keen, with a big Series A or early profitability, we’d probably make less. The founders, who had much more equity, could get rich if those things happened.

Back at the dining table later that day, I asked Dan if he thought that that was fair. Dan paused, smiled a tiny bit, and said, “We never said that you should do this for financial reasons. It’s risky. I could argue that the founders deserve more for taking on more of that risk, but I agree with your conclusions completely. You shouldn’t be doing this for the money.”

Kirk dropped an even-bigger weight onto the conversation when he added, “You’re asking me to give up about a half a million dollars.” Kyle was quick to respond. He looked at Kirk and said, “I think there are some pieces missing from your calculations. What’s the value of the experience you’re going to get from building a company? And you’re underestimating the value of the relationships you’re going to build, and the mentorship you’ll have through our investor network. And if it doesn’t work out, your experience here will make you even more valuable to the Amazons, Facebooks, and Googles of the world. I’m confident this is the best move you can make for your career.” We all sat back and thought about that for a bit.

Trying to wrap up the meeting on a lighthearted note, I began to slide my chair out from under the table and tried another half-joke: “I’ll join if Kirk joins!” We laughed and concluded the meeting. Kirk flew back to Seattle that night, and we were each left on our own to respond to the company’s offer.

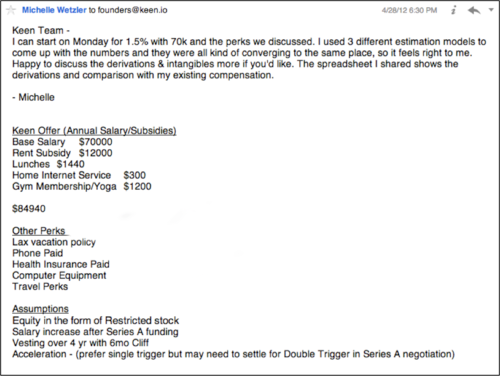

The next day, a Saturday, I sent the founders this email, including my analysis spreadsheet as an attachment.

My counter-offer had the following key points:

1. I asked for the highest salary option, but with triple the amount of equity Keen had offered.

2. I asked for equity in the form of restricted stock instead of common stock (In my research, I found there is a significant long-term gains tax advantage. If you’re interested, read more here).

I didn’t get a response for several days. Despite spending the weekend with the founders, I had no idea what they were thinking. I heard them discussing the offers in the living room a couple of times (I successfully avoided the temptation to eavesdrop).

Tuesday evening, finally, Dan asked me if I had a few minutes to chat, and we sat down across from each other in the living room. He said they had reviewed my counter-offer, and the founders decided that they thought 1.25% would be fair. That wasn’t quite the 1.5% I’d asked for, but it was still over double their original offer, so I was super happy. We talked about my request for restricted stock, and Dan told me they agreed with my reasoning. They decided to give this form of stock to all of the early employees. And that was that. We got up, and not really knowing any other way to end such a formal conversation, did an awkward handshake. A week later, we signed the official paperwork on real paper, with real ink (It felt very grown up!).

Kirk and Micah signed their letters that week, too, and we couldn’t be more happy with the outcome. We get to spend every day with people we love and admire.

Do you think I negotiated successfully? How would you evaluated this offer? Would love to hear your thoughts in the comments section.

– Michelle (@michellewetzler)

PS: The Keen founders told us transparency was one of their core values, and they continue to hold true to that. In addition to sharing all of Keen’s financial information with us during negotiation, they also agreed to let me post this story here (and even encouraged me to do so!). Another one of the reasons this is a great place to work 🙂