This post explains how we were able to dramatically reduce query latency for all query types by evolving our query architecture.

The Keen IO platform processes millions of adoc and batch queries daily, while maintaining a 99.9%+ uptime.

Improved Query Response Times

Let’s start with the results. Overall response times are more than half what they were before we made changes. The following graph shows the impact.

Improved Query Consistency

We have also made our query processing more robust by fixing a bug in our platform that could cause query results to fluctuate (different results for the same query) during certain operational incidents like this one.

The Magic of Caching

These dramatic results have been possible due to more effective caching of data within our query platform.

We’ve been working on improving query response times for many months and to understand the most recent update it would be useful to have a little background on how Keen uses caching and how it’s evolved over time.

Query Caching Evolution

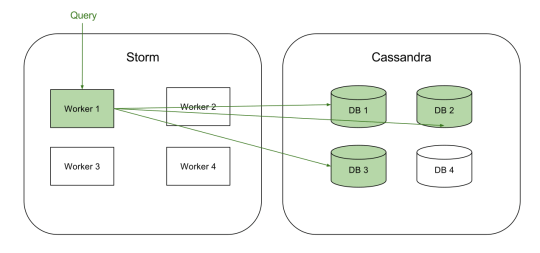

At the lowest level we have a fleet of workers (within Apache Storm) responsible for computing query results. Any query can be considered as a function that processes events.

Query = function(events)

Workers pull pending queries from a queue, load the relevant events from the database, and apply the appropriate computation to get the result. The amount of data needed to process a query varies a lot but some of the larger queries need to iterate over hundreds of millions of events, over just a few seconds.

If you want to know more about how we handle queries of varying complexity and ensure consistent response times I wrote a blog post on that earlier which is available at here.

(Simplified view of a Query being processed)

(Simplified view of a Query being processed)

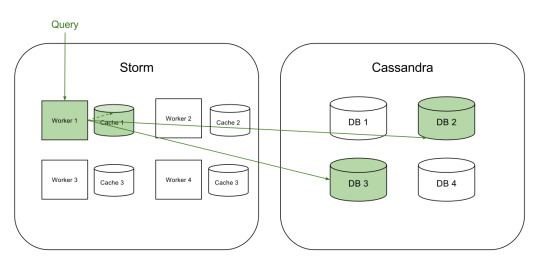

We started experimenting with caching about a year ago. Initially, we had a simple memcached based cache running on each storm worker for frequently accessed data. At this stage, the main problem that we had to solve was invalidating data from the cache.

Cache Invalidation

We don’t store individual events as individual records in Cassandra because that won’t be efficient, so instead we group events (by collection and timestamps) into what we call ‘buckets’. These buckets sometimes get updated when new events come in or if our background compaction process decides that the events need to be re-grouped for efficiency.

If we used a caching scheme that relied on a TTL or expiry, we would end up with queries showing stale or inconsistent results. Additionally, one instance of cache per worker means that different workers could have a different view of the same data.

This was not acceptable and we needed to make sure that cache would never return data that has been updated. To solve this problem, we

- Added a

last-updated-attimestamp to each cache entry, and - Set-up memcached to evict data based on an LRU algorithm.

The scheme we used to store events was something like the following:

Cache Key = collection_name+bucket_id+bucket_last_updated_at_

Cache Value = bucket (or an array of events)

The important thing here is that we use a timestamp bucket_last_updated_atas part of our cache key. The query processing code first reads a master index in our DB that gives it a list of buckets to read for that particular query. We made sure that the index also gets updated when a bucket is updated and has the latest timestamp. This way the query execution code knows the timestamp for each bucket to read and if the cache has an older version it would be simply ignored and eventually evicted.

So our first iteration of the cache looked something like the following:

(Query Caching V1)

This was successful in reducing load to Cassandra and worked for many months but we weren’t fully able to utilize the potential of caching because we were limited by the memory on a single storm machine.

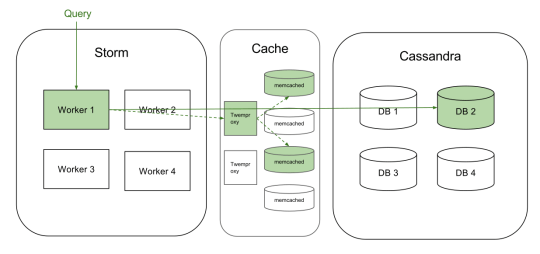

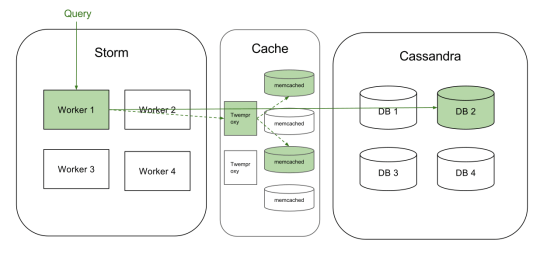

We went on to create a distributed caching fleet. We decided to use Twitter’s Twemproxy as a proxy to front a number of memcached servers. Twemproxy handles sharding of data and dealing with server failures etc.

This configuration allows us to pool the spare memory on all our storm machines and create a big, distributed-cache cluster.

(Query Caching V2)

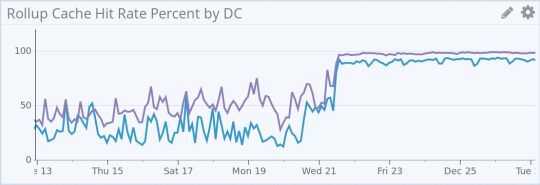

Once we rolled out the new configuration the impact was pretty dramatic. We saw a major increase in cache hit-rate and improvements in query performance.

(Improved cache hit rate after distributed caching rollout)

Improving Query Consistency

Keen’s platform uses Apache Cassandra, which is a highly available and scalable, distributed database. We had a limitation in our architecture and usage of Cassandra such that we were susceptible to reading incomplete data for queries during operational issues with our database.

Improved cache hit rates meant that most of the query requests were served out of cache and we were less sensitive to latency increases in our backend database. We used this opportunity to move to using a higher Consistency Level with Cassandra.

Earlier we were reading one copy (out of multiple copies) of data from Cassandra for evaluating queries. This was prone to errors due to delays in replication of new data and was also affected by servers having hardware failures. We now read at least two copies of data each time we read from Cassandra.

This way if a particular server does not have the latest version of data or is having problems we are likely to get the latest version from another server which improves the reliability of our query results.